Angélica María Pardo Chacón

Angélica María Pardo Chacón This post is part of a special series of Looking Ahead blog contributions by members of the Forum's Emerging Expert programs.

But why disarmament? The debate on the impact of weapons on gender-based violence prevention is a narrative that has been present in recent years, mainly encouraged by the feminist agenda. In some sectors the issue has made more progress than in others, and this month, on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women I would like to put into perspective some case studies and what we could continue to learn from them.

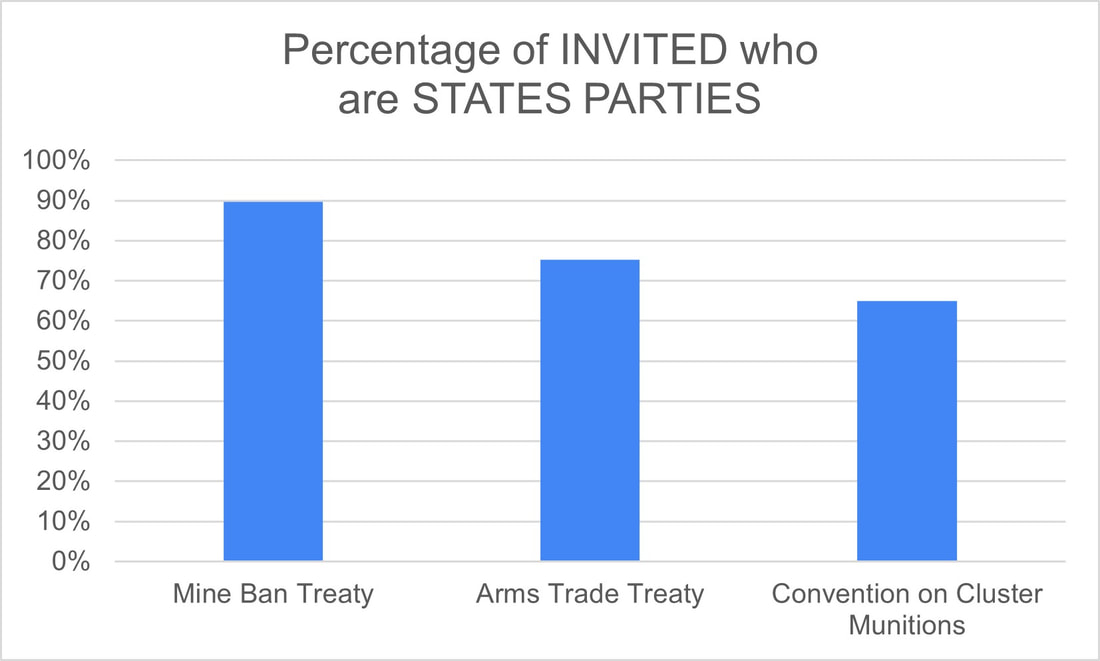

The international Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) regulates the international trade in conventional arms and seeks to prevent and eradicate the illicit trade and diversion of conventional arms. It is one of the first, if not the only one, to explicitly include in the text the risk of using arms to commit or facilitate serious acts of gender-based violence or serious acts of violence against women and children, as one of the elements to be evaluated for export authorization, included in other articles of the treaty. It is therefore natural that only four years after its entry into force, Latvia focused its work as chair of the treaty on the relationship between arms and GBV, issuing recommendations based on the Working Paper submitted by Ireland to the Conference of the States Parties to the Arms Trade Treaty: Article 7(4) and the assessment of GBV. Thus, since its inception ATT has been mindful of the impact of weapons in increasing the risk of GBV.

In the case of the Ottawa treaty, also known as the Convention for the prohibition of the use of anti-personnel mines, it has had several years of revisions and recommendations, both from civil society and the States parties aiming at the inclusion of the gender and diversity approach in mine action. Therefore, in the latest action plans of the convention, needs and strategies for the inclusion of the gender and diversity approach under the humanitarian principle of "leaving no one behind" are welcomed and proposed. This space also has advocacy groups such as the Gender and Diversity Working Group, which aims to promote inclusive and effective humanitarian interventions in mine action, through an intersectional approach, incorporating gender and other diversity factors mainly within the Convention on the Prohibition of Anti-Personnel Mines (APMBC) and the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM).

In this framework, and precisely this month, the gender program of the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research delivered a report taking stock of the Oslo Action Plan, in terms of the implementation of the action points related to gender and diversity.

Other examples and cases related to the inclusion of the gender and diversity approach could be discussed at greater length. Fortunately today, multilateral processes such as Stop Killer Robots, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, the Treaty of Tlatelolco, the Inter-American Convention Against the Illicit Manufacturing of and Trafficking in Firearms, Ammunition, Explosives and Other Related Materials (CIFTA) have included intersectional approaches.

All these experiences in the framework of humanitarian disarmament processes and multilateralism demonstrate the importance of gender mainstreaming and the prevention of gender-based violence in all international spheres and efforts. By recognizing gender equity and overcoming all types of violence and inequality as one of the Sustainable Development Goals, the issue has begun to acquire more relevance in multilateral spaces, but why mainstreaming the gender approach in international instruments could contribute to the prevention of gender-based violence?

Weapons are one of the expressions that humanity has historically found to promote "superiority", which for the purposes of this text we will not discuss. But if we take into account that war, in a very light analysis, has been defined from the absence of its counterpart, peace, it links elements of superiority, which has been traditionally linked to masculinity and its ability to exercise power.

It is not surprising, then, that the possession, production and use of weapons is identified as a real and useful mechanism in the search for that superiority, which has been at the head of patriarchal models, such as Mark Antony, Napoleon and other male figures who have been at the forefront of the arms industry. However, if we take into account that in contrast, peace is usually associated as a "soft, weak, vulnerable" practice, characteristics traditionally assigned to the feminine, it is to be expected that social disputes and the distribution of power, related to discourses and practices in international spaces, will also result in a masculinization of peace; This is why only having men in the room makes the real inclusion of strategies that mitigate the differentiated risks and impacts of weapons on women and diverse communities more distant and less rapid, maintaining glass ceilings.

But what does multilateralism have to do with it?

Bearing in mind that men are traditionally exposed to reproducing elements related to protection, having to show virility, strength and courage, it is to be expected that in the multilateral spaces for negotiation and consensus-building around disarmament, the need for men to comply with the patriarchal logic of "real men" hinders the generation of new ideas. If we add to this the lack of real representation of women and their vision, we find a longer road for the prevention of gender-based violence in these scenarios, since they continue to replicate unequal relationships in which women, children and LGBTTIQA+ community tend to be those who occupy the categories of vulnerability and low agency, while the symbolic dispute around the values attributed to the "feminine" and "masculine" permeate all processes and institutions.

In order to speak of effective multilateralism, among other things, we must speak of substantive representation, which implies a qualitative change during the consultation processes and the results of specific advocacy in favor of overcoming unequal relations. Although progress has been made in efforts to include a gender perspective, in the inclusion of women in delegations, in advocacy campaigns, women and their vision continue to be in the background in most processes and while there are strategies and processes that continue to appeal, unconsciously, to the superiority of the strongest - the strongest masculinized - weapons and the potential risk of their use continue to perpetuate dynamics of inequality that contribute to the increase of Gender Based Violence.

In this order of ideas, if we take into account that the spaces where international instruments are defined are par excellence scenarios of dialogue and socialization occupied mostly by political and social elites, in which men have the majority control, and that as a space for defining agendas and building international consensus there is still a greater male representation and agency, it is possible to identify that the road to prevention and attention to GBV is still ahead of us.

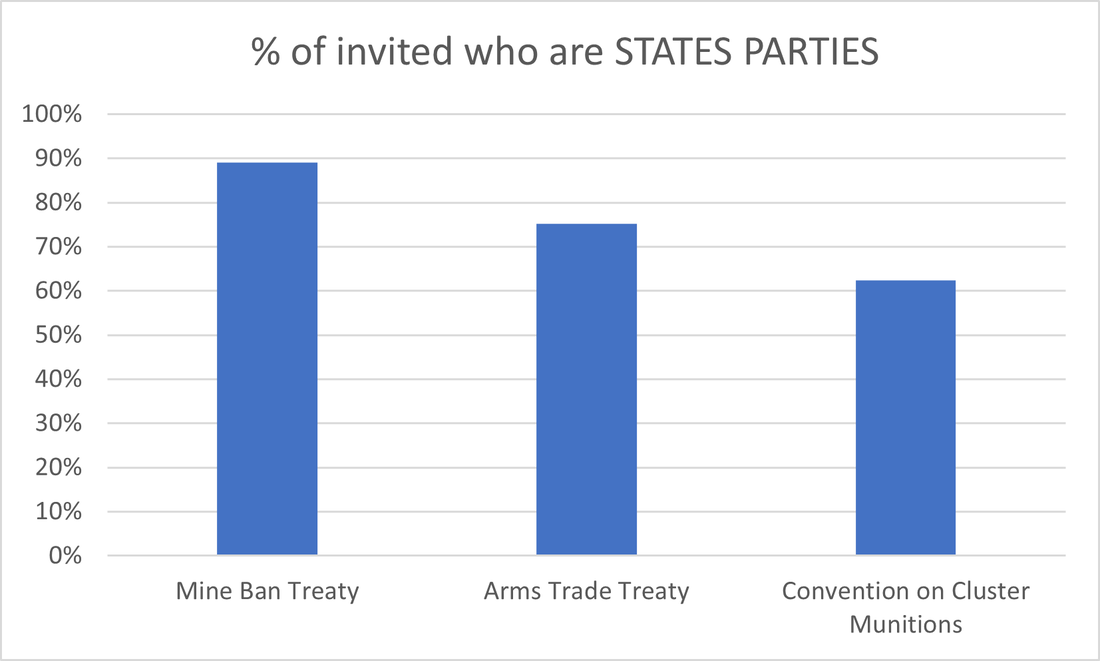

For this I would like to bring an experience with the Mine Action Fellows, a Mines Action Canada program (of which I am a part), at the States Parties meeting of the Ottawa 2022 convention. There, we decided to keep a tally of minutes of statements made by women in relation to those made by men; and the result was not surprising but alarming, women spoke less than 8% of the plenary time during 3 days! And yet, according to the research "Beyond Oslo: Taking Stock of Gender and Diversity Mainstreaming in the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention" conducted by the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, by 2022, 69% of the States attending the meeting of States Parties to the MBT recorded the participation of women in their delegations.

This is what I mean when I say that there is still much to learn, when we talk about effective multilateralism, we talk about representation, but also about the quality of that representation, which has been descriptive, counting percentages of participation but not the effectiveness of that participation.

Multilateralism in some humanitarian disarmament processes has made progress in recognizing the role of weapons in gender-based violence, but there is still much to be done in relation to substantive representation, the use of time, space and therefore the distribution of power in these spaces of discussion where agendas are defined and international consensus is built. Yes, we women are increasingly part of these spaces, but the voice and decisions continue to be made by the men in the room, who often have a masculinized, patriarchal and hegemonic vision of reality; this continues to mark the long road to talk about a real response from multilateralism to gender-based violence perpetuated by or in the context of the use of weapons, whether massive, indiscriminate, autonomous, or small arms and light weapons.

Angélica María Pardo Chacón is a political scientist from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana in Bogotá and currently is pursuing a master's degree in Global Affairs and Political Processes at the Universidad del Rosario. She is a member of the Women in Security and Defense in Latin America and the Caribbean network (Amassuru).

Inclusion on the Forum on the Arms Trade emerging expert program and the publication of these posts does not indicate agreement with or endorsement of the opinions of others. The opinions expressed are the views of each post's author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed