| This is the third blog post in a series looking at an array of issues in 2023 related to weapons use, the arms trade and security assistance, often offering recommendations. |

Despite hopeful steps taken in 2022, not least the late Autumn signing by over 80 states of Ireland’s Political Declaration in Dublin on the protection of civilians from the use of explosive weapons in populated areas (EWIPA), analysis of the explosive violence which characterised this turbulent year paints a bleak picture for the year to come.

In total, AOAV - which records global incidents of explosive violence from reputable English language media sources - listed 4,324 incidents of explosive weapon use around the globe in 2022, and 31,162 reported casualties. 67% (20,776) of those casualties were civilians.

This represents a 73% increase in recorded incidents of explosive weapon use from the 2,500 incidents recorded in 2021, and a corresponding 83% increase from the 11,343 reported civilian casualties in 2021. New conflicts, in particular Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the flare-ups between Armenia and Azerbaijan and Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, compounded ongoing conflicts and armed struggles in Ethiopia, Myanmar, Syria, Yemen, Somalia, and the Occupied Palestinian Territories, amongst others. Many of these armed conflicts have created desperate humanitarian crises which will carry over into 2023.

More specifically, air-launched attacks rose by 17% between 2021 and 2022, from 441 to 517 recorded incidents, while ground-launched attacks increased by 187%, from 792 to 2,272 recorded incidents. IED attacks decreased by 13% between 2021 and 2022, from 1,033 recorded incidents to 897.

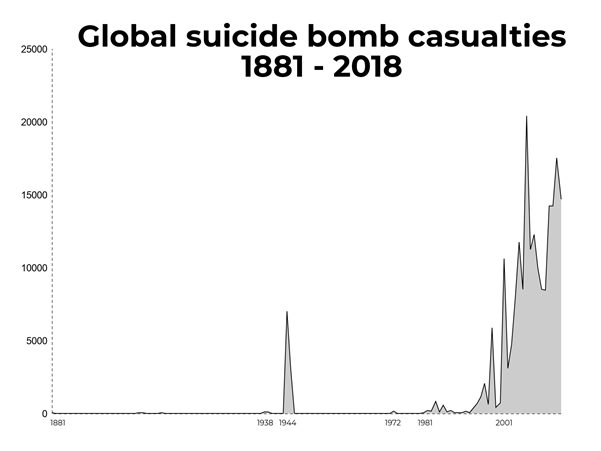

Correspondingly, explosive weapon use attributed to state actors rose by 228% in 2022, from 807 recorded incidents in 2021 to 2,644 over this past year, while incidents attributed to non-state actors remained consistent, decreasing by 3% from 1,370 incidents in 2021 to 1,334 in 2022. It seems likely, then, we will see more state-sponsored violence in the year to come and less so-called ‘terrorism’.

The distinction between civilians and armed combatants has continued to grow increasingly blurred. In the Myanmar context, civilians mobilised in response to the coup and the military regime’s oppression of the population, and in Ukraine, civilians are able to provide information to the Ukrainian army via apps on their smartphones. In Somalia, villagers have organised themselves into vigilante groups to resist Al Shabaab. The systematic targeting of civilian infrastructure in support of the war effort has been consistently visible in Myanmar and Ukraine. Rather than enhancing the principle of distinction and keeping civilians removed from armed conflict, the increasing ‘civilianisation’ of armed conflict, including growing reliance on private security companies, promises that civilians and civilian infrastructure will continue to be central in armed conflicts globally.

This is reflected in the fact that incidents of explosive weapons used in populated areas increased by 108% between 2021 and 2022, from 1,436 recorded incidents to 2,986, and civilian casualties from such rose by 86% (from 10,518 to 19,599).

EWIPA accounted for 69% of incidents recorded in 2022, and caused 94% of civilian casualties. AOAV recorded 668 incidents of non-state actors using explosive weapons in populated areas in 2022, compared to 731 in 2021 - a 9% decrease. On the other hand, incidents of state actors using explosive weapons in populated areas rose by 311% in 2022, from 518 to 2,129 recorded incidents.

With ongoing conflicts entering into 2023, the coming year looks set to continue the upward trend in incidents of explosive weapon use. Actors will remain actively embroiled in the complex, intractable conflicts which have come to characterise this decade, and in which state actors and their non-state proxies fight on multiple fronts, often in or near to populated civilian areas.

ZONES OF CONFLICT

There are several conflict areas, including both international and non-international armed conflicts, which are likely to continue to experience intensive explosive weapon use over the coming year, severely impacting civilians and civilian livelihoods.

Ukraine

AOAV recorded 1,853 incidents of explosive weapon use in Ukraine in 2022, a 1,585% increase compared to the 110 incidents recorded in 2021. Those incidents resulted in 10,381 reported civilian casualties in 2022, or a 36,975% increase from the 28 civilian casualties reported in 2021. This is likely under-reporting as AOAV only collects data from single-reported incidents as reported in reputable media, and cannot include collective assessments.

The USA and Europe continue to provide and pledge military and non-military aid to Ukraine, while relations between the USA and Russia have reached an all-time-low after a tense and difficult year. Deep rifts, political intransigeance, misinformation, and mistrust continue to make communication and diplomacy highly challenging. For these reasons, it is likely that Russia will maintain or even increase the intensity of air- and ground-attacks in Ukraine in 2023, continuing to target essential civilian infrastructure.

Ground-launched weapons accounted for 81% (1,494) of recorded incidents of explosive violence in Ukraine, and caused 76% (7,481) of reported civilian casualties, while air-launched weapons accounted for 6% (104) of incidents and 15% (1,541) of civilian casualties. Consistent ground shelling is likely to remain a defining feature of the conflict in Ukraine and cause civilian casualties on a daily basis in towns and villages, while more sporadic air-launched attacks continue to result in discrete mass casualty events.

Afghanistan

Following the Taliban take-over of Afghanistan in August 2021, the armed group claimed it would clamp down on extremist violence in the country, but 2022 has been a painfully injurious year for civilians. ISIS-K, the IS affiliate in Afghanistan, perpetrated deadly attacks throughout the year, and other groups continued to target both civilian and military infrastructure. Sunni muslims and educational facilities have been particularly targeted by ISIS-K and other groups.

While 2022 saw an 80% decrease in incidents of explosive violence in Afghanistan compared to 2021, from 458 recorded incidents to 90, and a corresponding 57% decrease in reported civilian casualties (AOAV recorded 3,051 civilian casualties in Afghanistan in 2021, and 1,312 in 2022), IEDs continue to be a leading cause of civilian harm in the country. They accounted for 64% (294) of recorded incidents and 77% (2,347) of reported civilian casualties in 2021, and 76% (68) of incidents and 85% (1,119) of civilian casualties in 2022.

The Taliban have so far failed to deliver on the promise of bringing stability to the country and adequately protecting minority groups and the right to education. It is consequently likely IEDs will continue to be the predominant cause of civilian harm in Afghanistan in 2023, and Sunni muslims and educational facilities will continue to be at particular risk.

Syria

The conflict which has plagued Syria since 2011 shows few signs of coming to a close in the coming year, and the invasion of Ukraine has made an already-complex context even more fraught. The rise of IS after their supposed defeat in 2018, the intensifying tension surrounding the Kurdish community, and the polarisation of relations between the USA, Russia, Israel and Iran, each of whom back armed groups in Syria, all speak to the intensification rather than de-escalation of the conflict. In 2022, AOAV recorded 652 incidents of explosive weapon use in Syria, compared to 709 in 2021, and 1,309 civilian casualties (down from 2,016 in 2021). This downward trend has been observable since 2017, when 1,750 incidents were recorded and 13,062 civilian casualties reported. If this pattern holds, 2023 should see a decrease in the number of recorded incidents and civilian casualties.

Ground-launched weapons accounted for 47% (304) of recorded incidents of explosive violence in Syria in 2022, and caused 55% (715) of reported civilian casualties, while IEDs accounted for 23% (148) of incidents and 12% (151) of civilian casualties. Air-launched weapons, which accounted for 19% (129) of recorded incidents, caused 23% (296) of civilian casualties. Given the continuing activity of both state and non-state actors across Syrian territory, both IEDs and manufactured weapons will most likely continue to cause civilian harm, with ground shelling remaining the dominant form of civilian harm in Syria in the coming year.

Somalia

In 2022, the Somali government intensified their fight against Al Shabaab, mobilising the broader population and leaning on US air support. Based on data recorded by AOAV in 2022, Al Shabaab and other armed groups responded by intensifying their own attacks on civilian and military infrastructure.

AOAV recorded 89 incidents of explosive weapon use in Somalia in 2021, compared to 95 in 2022 - a 7% increase. Correspondingly, the 1,222 reported civilian casualties recorded by AOAV in 2022 represent a 128% increase from the 537 civilian casualties recorded in 2021. At the time of writing, there has been no military breakthrough or suggestion of a diplomatic solution, leading AOAV to understand the situation will continue as is or escalate in the coming year.

Of note, incidents of IED attacks in Somalia decreased by 17% between 2021 and 2022, from 66 to 55 recorded incidents, but civilian casualties of IED attacks increased from 425 to 1,091, or by 158%. IED attacks consequently became more targeted and injurious in 2022 compared to 2021. Additionally, incidents of reported mine explosions, which are likely to also include directly-emplaced IEDs, increased by 650% between 2021 and 2022, from two to 15 recorded incidents, and caused 50 civilian casualties in 2022 compared to 14 in 2021. As the military conflict continues and both sides remain resistant to a diplomatic solution, the use of IEDs to target civilians and civilian infrastructure is likely to continue.

Myanmar

In 2022, AOAV recorded 551 incidents of explosive weapon use, a 430% increase compared to the 104 incidents recorded in 2021. Similarly, 2022 witnessed 983 civilian casualties, a 178% increase from the 353 civilian casualties reported in 2021.

The military coup in February 2021 devolved into a non-international armed conflict affecting the majority of the country. Established Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs) intensified attacks against the new military government, and civilian defence forces were formed to resist the junta, some loosely allied under the shadow National Unity Government. The military’s response has been to target villages in air strikes and ground-attacks, resulting in an escalating humanitarian crisis. Armed groups are intensifying their attacks against the military government and suspected collaborators, and demonstrating the ability to learn quickly and adapt their military strategy, while the military government continues to implement the established ‘Four Cuts’ strategy, targeting civilian networks which support the opposition.

Ground-launched weapons accounted for 32% (179) of recorded incidents of explosive weapon use in Myanmar in 2022, and 56% (553) of reported civilian casualties. IEDs accounted for 20% (112) of incidents, and 12% (114) of civilian casualties, while air-launched weapons accounted for 9% (52) of incidents and 21% (202) of civilian casualties. Mines accounted for 34% (185) of incidents, and 7% (202) of civilian casualties. Manufactured weapons, especially ground-launched weapons, will likely continue as the dominant form of civilian harm in the year to come as the military government maintains its current strategy and goals.

Pakistan

In 2022, AOAV recorded 126 incidents of explosive weapon use in Pakistan, a 26% increase from 100 recorded in 2021. Reported civilian casualties of explosive violence in Pakistan increased by 59% in 2022, from 445 to 706. Developments in Pakistan, where the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) called off the May ceasefire in November 2022, will likely lead to an increase in incidents of explosive violence, notably IED attacks. This trend was already visible in December, when AOAV recorded 54 civilian casualties of IEDs, the highest number recorded since March 2022.

IEDs accounted for 52% (65) of recorded incidents of explosive weapon use in Pakistan in 2022, and caused 74% (521) of reported civilian casualties. Civilian casualties of IEDs in Pakistan rose by 69% in 2022, from 308 civilian casualties of IEDs reported in 2021. Ground-launched weapons accounted for 45% (57) of incidents and 25% (173) of civilian casualties. In particular, grenades thrown by unknown non-state actors represented 38% (48) of incidents and caused 19% (134) of civilian casualties. IEDs will likely continue to cause the majority of civilian harm as a fragile peace crumbles.

COVID-19

Analysis of AOAV data across the years impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic shows a marked decrease in recorded incidents and civilian casualties of explosive violence. In 2020, AOAV recorded a 24% decrease in incidents compared to 2019, from 3,816 to 2,909, followed by a further 14% decrease to 2,500 recorded incidents in 2021. Similarly, there was a 43% decrease in reported civilian casualties from 2019 to 2020, from 19,401 to 11,055 followed by a 3% increase to 11,343 civilian casualties in 2021. There are myriad factors which could have influenced the way COVID-19 impacted explosive weapon use globally, from lockdowns and restrictions to cultural attitudes towards illness and the virus.

AOAV recorded a 59% decrease in incidents of air-launched weapon use between 2019 and 2020, from 1,305 to 529 incidents, and a further 17% decrease to 441 incidents in 2021. Similarly, incidents of ground-launched weapons decreased by 11% between 2019 and 2020, from 1,067 recorded incidents to 949, and by another 17% to 792 incidents in 2021. Recorded IED attacks dropped by 4% between 2019 and 2020, from 1,230 to 1,176 incidents, and by a further 12% to 1,033 incidents in 2021.

However, data collected by AOAV in 2022 shows a general reversal of this trend. As mentioned previously, recorded incidents of explosive weapon use rose by 73% between 2021 and 2022, and reported civilian casualties similarly rose by 83%. Air-launched attacks rose by 17% in 2022, while ground-launched attacks increased by 187%. IED attacks, on the other hand, have continued to decrease, dropping by 13% in 2022. This upward trend is in no small part due to conflicts which escalated or began during and after the COVID-19 lockdowns, such as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the military coup in Myanmar, but it is also likely that, as restrictions continue to ease, the legal and illegal networks which facilitate explosive violence will gather momentum. As has been noted elsewhere, 2023 might prove to be a bumper year for arms sales. Civilians be warned.

Iain Overton is Executive Director at the London-based nonprofit Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) and an expert listed by the Forum. Chiara Torelli is lead explosive violence researcher at AOAV.

Inclusion on the Forum on the Arms Trade expert list and the publication of these posts does not indicate agreement with or endorsement of the opinions of others. The opinions expressed are the views of each post's author(s).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed