| On April 4, 2019, Iain Overton's The Price of Paradise: How the Suicide Bomber Shaped the Modern Age was published. The Forum on the Arms Trade interviewed Overton (Executive Director, Action on Armed Violence [AOAV]) to ask about key findings, ways to think about suicide bombings, and suggestions for how to approach curbing their frequency. His answers are featured in this Looking Ahead blog entry. Question: What are the trends you are finding? |

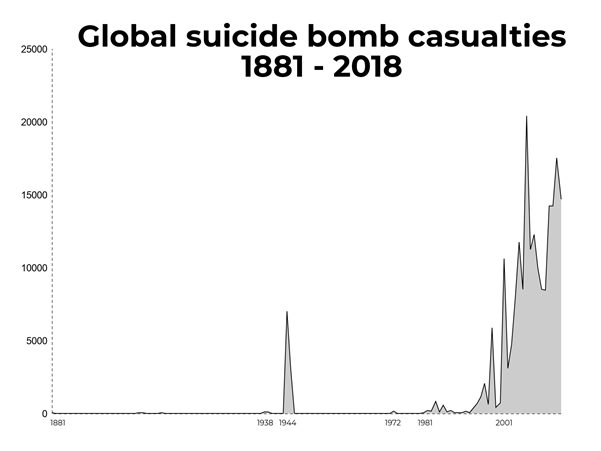

The most notable fact – and the reason I wrote the book – has been that of a major shift towards suicide bombing use, especially in the last decade both in terms of attacks and casualties. More than 40% of all people killed by suicide bombers since their first use against the Tsar of Russia in 1881 have happened in the last five years.

This is in large part because of a major spike in attacks by Salafist jihadists. Such a dark trend has, though, deep historical roots. In the book I argue that ISIS is, effectively, the sum of the parts of previous suicide bomb campaigns. It has elements of the utopianism of the Russia revolutionaries of the 19th century; the militarism of the Japanese kamikaze; the Islamic notion of sacrifice as developed in Iran under the Ayatollah Khomenei; the strategic logic of Lebanese terror groups; the targeting of civilians as seen by Hamas; the cult of the leadership as seen under the Tamil Tigers; and the millenarianism and global conflict as summed up by Al Qaeda. In addition to this, though, modern day Salafist jihadist suicide bombers have a profound sense of ‘end of days’ – a millenarian logic that means, to those bombers, death is loved more than life and their sacrifice is integral to the creation of a glittering Islamic future.

This is right. The suicide bomber does not fit neatly into international arms control and, as such, it is the ever-growing elephant in the room. It is the deadliest of all improvised explosive devices (IEDs), and IEDs themselves are the cause of the greatest civilian harm of all explosive weapons – at least since 2010.

IEDs themselves pose a fundamental challenge. After all, only about 15% of all victims from landmines and ERW have, in recent years, been from the traditional manufactured landmine, but the global approach to landmines has not changed substantially in response to this.

Suicide bombs rely on improvised components. Some component parts - such as detonators and certain chemicals – certainly need more attention in terms of international border sales control. But it goes deeper than just precursor control. Overall, the suicide bomber offers up an existential crisis to some degree to the UN and the disarmament community. The solution cannot be to ban production.

Furthermore, modern day suicide bombers use ideology as a weapon that, in itself, poses challenges for members of the disarmament community who have impartiality rooted in their DNA.

I believe one reason for the proliferation of this form of weapon is that it side-steps UN arms controls; it doesn’t fit neatly into funding streams to challenge its spread; it is largely ignored in places such as the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) and [UN General Assembly] First Committee; and it doesn’t have strong voices among civil society seeking to address its harm.

The reasons for these short-comings are understandable and complex, but given the harm from suicide bombers, the silence that surrounds the suicide bomber in terms of high-level debate at the UN and elsewhere is deafening. Responses to it are not coordinated and where they are, they are often under-funded and under-valued.

In a sense the complexities of challenges that the suicide bomber poses to the disarmament community is, in part, one of its devastating strengths. And those who say the existing processes are already in place to stop such a terrible weapon from spreading, should follow up their statement by saying that those processes are clearly not working.

There are many individual and group steps taken on the path to most suicide bombings. These are complex and diverse. Some involve individual motivations of revenge, depression, hopelessness and fear. Some involve groups believing in utopianism, militarism, sacrificial justice, the right to target civilians and the need to attack those they deem heretics and apostate.

But just as there are many steps to a suicide bomber, there need to be steps away from such as well.

To prevent calls by those who might use bombs to act out of revenge, nation states need to uphold human rights; they need to ensure that breeding grounds for extremism are not created in prisons, schools or mosques; they need to combat Islamophobia; to insist that the trials and punishments of Muslims accused of terror are subjected to a transparent and fair process; to address high levels of unemployment and widespread socio-economic deprivation among many Muslim communities; to create victim-assistance programmes; and to recognise the fact that many societies around the world have concerns about immigration and the failures of liberal policies on race and religion.

This list could go on. Countering extremism on all sides is notoriously hard. When the then Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon revealed the UN’s plan of action to do so in January 2016, there were over seventy recommendations made, ranging from development policy initiatives, to youth empowerment, to gender equality to human rights.

But there are four fundamental points that I believe should be addressed head-on.

The first is that the United Nations needs to up its game. A ban on suicide bombing would send out a clear message of priorities, and create political commitments and funding to address the complex issues that underpin the weapon’s rise. This needs to spread beyond demining operations – any approach has to accept suicide bombings are built upon both social and ideological grounds. And funding could help charities, businesses, trade officials, police units, UN agencies, militaries and others come together to respond imaginatively and creatively to this terrible weapon. Without there being a coherent and systemic approach to combating the cult of the suicide bomber, there is little hope the spread of this weapon will be curtailed.

The second point is that we should seriously assess the impact Western foreign policy has had on the Middle East and North Africa to avoid past mistakes. This does not mean accepting the conspiracy-laden narratives presented by jihadists. Nor is it realistic to assume that Western policies towards the region going back for decades can be completely altered. But the inadvertent arming of future jihadi groups through the US’s and other states’ oftentimes uncontrolled supply of arms and explosives to the Middle East should be stopped. Air strikes have been shown, repeatedly, to fuel support for Salafi-jihadism, while carrying out secret drone strikes bolsters the claims the West is waging an eternal, subversive battle against Islam. These must be ended.

The third challenge lies in stopping the conflicts in which the vast majority of today’s suicide bombings and their casualties are found. Some nation states have focused on state-building activities to do this, with some in the West initiating violent regime change to induce democratisation and economic growth. They do so believing peace can be built by creating democracies, but after two decades this approach has failed to work. Partly this is because you cannot export democracy down the barrel of a gun. Partly because such interventions fail to take into account the political reality of the Middle East, specifically the Arab states. Traditional Arab-Islamic concepts of war and peace seem more based on immediate conflict resolution, seeking a return to the status quo, than wholesale transformation and reform. Peace-building initiatives need to reflect the cultural conditions of the region, and not merely act as a ‘sticking plaster’ of Western sensibilities.

Fourth, states should be profoundly aware of the failures of history when it comes to countering suicide bombers. Much of the media might seek hard and retributive justice, but history has shown that man’s ability to overstep the mark, generate mission creep and abuse human rights in the name of national security is all too predictable. The conditions to produce a suicide attack are complex: the means to counter such attacks need to be as well.

In the end, it is in our own responses to suicide attacks where we have the most significant capacity to act. When we look back to find out how we arrived at the place we find ourselves in now, we should not be blinded by the carnage brought by terrorism, but also see the ensuing violence justified to crush that threat. We must remind ourselves how the Tsar’s blind repression of anarchists fanned the flames of tyrannical Communist revolt. How the US high command’s justification for the devastating use of nuclear weapons to defeat the feared kamikaze ushered in the Cold War. And how the calamitous invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan were decided before the dust had settled on downtown Manhattan.

That suicide bombing campaigns have often had, through history, singular characteristics and these can be traced from its first inception to the modern day. That stating suicide bombing is a Muslim problem fails to recognise that the Russians invented suicidal terrorism, the Chinese invented the suicide belt, the Russians used suicide bomb planes before the Kamikaze, that the Sri Lankans were once the deadliest users of suicide bombs in the world, and that – throughout history – Christians, Buddhists, Sikhs and others have all used this form of terror. Ideology is a driving force behind suicidal terror, but that ideology is not unique to Salafist jihadism.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed