| This is the second blog post in a series looking at an array of issues in 2022 related to weapons use, the arms trade and security assistance, often offering recommendations. |

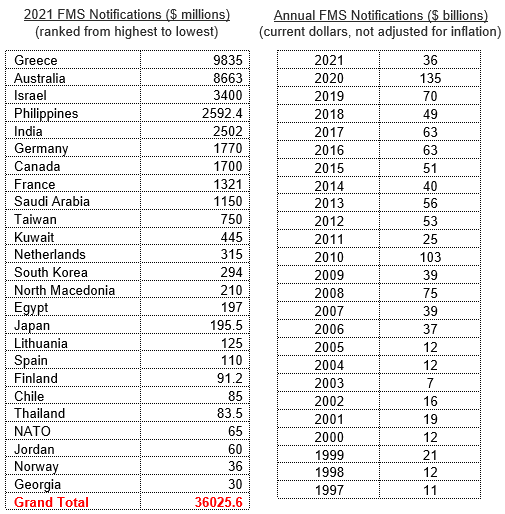

While the 2021 total is the lowest in a decade, there are still many problematic sales on last year's list. Top of mind is the one that raised the most attention -- the $650 million November notification of 280 air-to-air missiles to Saudi Arabia. The administration argued that those weapons could not be used for "offensive" purposes and therefore were in line with its human rights goals, especially as related to avoiding harm to civilians in Yemen. Nonetheless, a majority of the President's party voted (unsuccessfully) to block the sale in the Senate last month, with many arguing that providing weapons to oppressive regimes serves to legitimize them, regardless of whether you consider weapons offensive or defensive.

Those arguments can and should also be applied to others on last year's list, perhaps most noticeably the Philippines, where the administration told Congress it wanted to sell F-16s, Harpoon and Sidewinder missiles valued at more than $2.5 billion to the oppressive Duterte regime. Scrutiny is also rising on countries that have in the past been less controversial, such as Israel and India, for which there were FMS notifications as well as human rights concerns.

It's Not Just Foreign Military Sales (FMS)

FMS itself also does not tell the full arms sales picture, which appears to be increasingly comprised of company-initiated Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) that are much less transparent to the public. The May scandal of JDAMs on offer to Israel during a flare up of conflict in which civilian areas were bombed was via the DCS program. Part of the controversy was that a Congressional leak was needed to raise awareness of the potential deal, in part because DCS notifications are not shared on a convenient website, whereas FMS notifications are.

The State Department arms sales factsheet from January 2021 indicates both the scale and relative lack of information we have on the DCS program. It details that in fiscal year 2020 more than $124 billion in DCS licenses were authorized, but only $38.5 billion of which were notified to Congress. (In the latest factsheet, released last month, the Biden administration provides even less clarity, removing details about how much of the $103.4 billion fiscal year 2021 DCS approvals were notified to Congress.)

There is also a billion dollar request for Israel's Iron Dome program supported by the administration, assistance to Egypt that the Biden administration did not fully withhold, and $20+ billion F-35 and drones sales to the UAE that raise the question of how much restraint this administration will support.

New Policy Anticipated

As soon as this month, we expect the Biden administration to unveil a new conventional arms transfer policy that was previewed in part in November. At that time, Tim Betts, the Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, said the policy will "seek to elevate human rights, stress the principles of restraint and responsible use." That is certainly welcome. In all likelihood, however, the new policy will follow earlier ones in that the list of reasons to engage in weapons transfers will not be weighted. Those looking to argue for commercial interests will find language they want, and no indication that human rights have a higher priority. How the administration actually implements the policy will likely be more telling than the words in it.

An initial follow-on step should be for the Biden administration to recommit to the U.S. signature to the Arms Trade Treaty. President Trump’s repudiation of the one global treaty that establishes baselines for responsible trade of broad categories of conventional weapons, and which is already consistent with U.S. law, is a stain on U.S. international credibility and inconsistent with shared goals.

More to Watch

Getting this right is not easy, of course. But if the United States, the world’s largest weapons provider by far, actually wants to show arms transfer restraint, it needs a consistent approach to existing or future conflicts that moves away from adding more weapons to volatile situations. It must find ways to engage the Middle East and elsewhere through commercial ties, cultural and academic connections, and other approaches. And in many cases, especially in pulling back, it will need to increase and enable humanitarian assistance to those places impacted by war. The withdrawal from Afghanistan, while a positive for those supportive of a less militarized approach, has not been followed by a humanitarian response sufficient for the suffering country.

Nor has aid that would help those in Yemen been able to reach them, in part because the United States has not truly used its full power to demand that the blockade on the country be immediately ended. In Yemen, the Houthi are no saints. They have committed horrible abuses. U.S. leverage and complicity, however, is tied much more closely to Saudi Arabia, for which the U.S. continues vital aircraft maintenance support, and to the UAE, which despite claims of exiting the war is still engaged via proxy groups and control of the Socotra island.

Even more than relations with Saudi Arabia, that with the Emiratis may be most telling on potential U.S. arms restraint in the coming months and years. In December, the UAE threatened to walk away from the massive F-35 deal. The administration has consistently said it wants to make the deal work, but has insisted on publicly unspecified end-use and other conditions. In my close reading of the comments by State Department and Defense Department officials last month, it’s unclear that human rights and civilian protection concerns are being raised at all with the Emiratis. That must change.

Finally, Congress may also play a role. A wide array of legislation has been introduced that would impact on arms trade restraint should it be adopted. A short, but incomplete, list includes the progressive Stop Arming Human Rights Abusers Act introduced by Rep. Ilhan Omar; the SAFEGUARD Act, led by the influential chairs of the House Foreign Affairs and Senate Foreign Relations committees; and the bipartisan National Security Reforms and Accountability Act/National Security Powers Act that would “flip the script” and require Congressional approval on many arms sales -- similar to an approach once introduced by then-Senator Joe Biden in the 1986.

Jeff Abramson is a senior fellow at the Arms Control Association and manages the Forum on the Arms Trade

RSS Feed

RSS Feed